Educators’ experiences and strategies for responding to ecological distress

Blanche Verlie, Emily Clark, Tamara Jarrett & Emma Supriyono.

Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 2020, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 132-146. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2020.34

Abstract

Research is increasingly identifying the issues of ecological distress, eco-anxiety, and climate grief. These painful experiences arise from heightened ecological knowledge and concern, which are commonly considered to be de facto aims of environmental education. Yet little research investigates the issues of climate change anxiety in educational spaces, nor how educators seek to respond to or prevent such emotional experiences. This study surveyed environmental educators in eastern Australia about their experiences and strategies for responding to their learners’ ecological distress. Educators reported that their students commonly experienced feeling overwhelmed, hopeless, anxious, angry, sad and frustrated when engaging with ecological crises. Educators’ strategies for responding to their learners’ needs included encouraging students to engage with their emotions, validating those emotions, supporting students to navigate and respond to those emotions, and empowering them to take climate action. Educators felt that supporting their students to face and respond to ecological crises was an extremely challenging task, one which was hindered by time limitations, their own emotional distress, professional expectations, society-wide climate denial and a lack of guidance on what works.

Introduction

Research is increasingly documenting the psychological, emotional and inter/personal impacts of climate change (Hayes et al., 2018; Tschakert et al., 2019). Young people are especially vulnerable to ecological distress (Pihkala, 2019; Ojala, 2012b). They are the generation who will inherit the escalating ecological crises that are latent within the climate system (Corner et al., 2015; Whitehouse, 2013) and who will be challenged with the wholesale transformation of the world’s economy (IPCC, 2018). For decades, environmental education has sought to increase people’s ecological knowledge and concern (e.g. UNESCO, 1977), however, this can heighten climate anxiety (Kelsey, 2017; Pihkala, 2019; Ray, 2018) and can evoke a profound mix of emotions including anger, fear, worry, hopelessness, grief, and disillusionment (Albrecht 2011; Ojala 2016; Pfautsch & Gray 2017; Strife 2012; Verlie 2019a). Youth climate strikes have, in the past two years, mobilized millions of young people around the world and demonstrate that young people, as a generation, are not dismissive of ecological degradation (Grauer, 2020). Perhaps it is time to move beyond the ‘concern deficit’ model of environmental education (Siperstein, 2015; Stevenson & Peterson, 2016), towards one that recognizes that denial and disengagement often arise not from disinterest but as a method to protect the self from engaging with information that is ‘too disturbing’ (Norgaard, 2011, p. 61).

We believe it is imperative to understand how young people cope with the emotional toll of climate change and how they can be supported to do so. Education plays a pivotal role in young people’s lives and as such, is uniquely placed to support young people in coming to terms with, preparing for, and living with the futures they will inherit. Further, research and innovation in education has the potential to guide other efforts throughout society to support people to navigate climate anxiety, such as those implemented by communicators, artists, governments, environmental NGOs, community groups and activists. Educators are often afforded significant time for face-to-face and care-oriented relations with people and are therefore potentially better placed than most to attune to the complexities of people’s experiences of climate anxiety over time (Chapman, Lickel & Markowitz, 2017). Therefore, this research aims to explore the experiences, insights, and strategies of a sample of Australian environmental educators who have attempted to respond to their learners’ ecological distress, with a view to sharing valuable practices that others can implement and experiment with. We invited educators to respond to a short online survey in September 2019 that included both multiple choice and free-text answers. The survey explored how the educators perceive their students’ emotional states, their experiences of exploring or responding to ecological distress, and their suggestions for how best to do so. While these educators offered valuable insights and strategies, they also indicated that this work is highly challenging for them.

Literature Review

Research is increasingly identifying that climate change is taking a psychological and emotional toll on people, and that young people are especially vulnerable to this (Cianconi, Betró & Janiri, 2020; Manning & Clayton, 2018). While this can occur through direct experience of extreme weather or climatic disasters, knowledge of the overarching existential threat is also deeply distressing for people (Affifi & Christie, 2019; Hayes et al., 2018; Ojala, 2012a; Pihkala, 2018). Engaging with climate change has been found to cause a range of intense emotions, such as worry, anxiety, grief and anger, often coupled with feelings of guilt or hopelessness (Ojala, 2016; Pfautsch & Gray 2017; Verlie, 2019a). Young people especially are forced to grapple with the challenges climate change poses to their identity, their place in society and their future (Moss & Wilson, 2015; Verlie 2019a). While these dimensions of ecological distress should not be pathologized (Verplanken & Roy, 2013), climate anxiety can intersect with and contribute to mental illness (Hayes et al., 2018). This leads to one of the key challenges when teaching climate change: greater knowledge of climate change can induce hopelessness, disillusionment or apathy (Kelsey, 2017; Ray, 2018). Albrecht (2011) defines this phenomenon as eco-paralysis: when people care too much about climate change but feel unable to do anything effective, they can engage in avoidance as a psychological defence (Head, 2016; Kristin & Dilshani, 2018). While this can be correlated with positive psychological outcomes in the short term, in the long-term such strategies are counterproductive (Ojala, 2012a; Taylor & Stanton, 2007).

This raises the question of how people can be practically supported to face up to ecological crises and the distress they cause, and environmental education is perhaps the arena best placed to offer this. Emotional work is often dominated by psychological approaches and the proliferating research on climate change as a mental health issue confirms this (e.g. Cianconi, Betró & Janiri, 2020; Manning & Clayton, 2018). But climate anxiety is not an illness or disorder, but an appropriate and even valuable source of discomfort that can provide an important lens to help people re-evaluate what is important to them and find meaningful ways to inhabit the world (Ojala, 2016; Siperstein, 2015; Verlie, 2019a). Rather than therapy to soothe or heal these feelings (which is not even possible given the escalating nature of the crises [Kelsey, 2017]) perhaps what is needed are strategies to help people direct them in productive ways (Affifi & Christie, 2019). Education’s remit for cultivating critical thinking and empowerment thus makes it an exciting realm for supporting young people to contribute to what Verlie (2019a) terms ‘bearing worlds’: engaging with the pain that the status quo offers in order to transform it. However, relatively little environmental education literature has investigated ecological distress, climate grief or eco-anxiety (Kelsey, 2017) meaning there are major gaps in our understanding of these issues and an urgent need for more research.

One of the key issues that the existing literature does identify is the need to balance honest representations of the catastrophic realities of climate change without overwhelming people to such an extent that they disengage. Cultivating hope in students is being recognised as crucial to inspiring and sustaining the collective and widescale changes needed (Kelsey, 2017; Li & Munroe, 2018; Nairn, 2019; Russel & Oakley, 2016). However, because feelings of hope can in fact arise from denial (Ojala, 2015), an overemphasis on positive messages can lead to inaction (Hornsey & Fielding, 2016). While terminology differs (e.g. ‘radical’, ‘critical’, or ‘constructive’ forms of hope), most agree that ‘the pivot point of transformation’ (Hayes et al., 2018, p. 35) is what we, following Macy and Johnstone (2012), are calling ‘active hope’: when people believe that things need to change urgently, that this is only possible if they actively engage in efforts to make such changes, and that their efforts will be at least somewhat effective (Lehtonen, Salonen & Cantell, 2019; Li & Monroe, 2019; Siperstein, 2015). This is hope as a practice: not just a feeling, but action that emerges from and contributes to that feeling. However, while active hope can be self-reinforcing (Kelsey, 2017) over the longer term, in order to motivate it environmental educators are faced with the task of uncovering and mobilizing their students’ anxiety in the short term (Ojala, 2016), which, when situated within systemic and pervasive climate denial, can lead to perceptions that they are ‘stealing childhood’ (Grauer, 2020) or otherwise harming children (Affifi & Christie, 2019; Amsler 2011; Ecclestone & Hayes 2008), or even to accusations of child abuse. As research has shown, the complexity and controversy of climate change can make it difficult for educators to teach holistically in classrooms (Herman, Feldman & Vernaza-Hernandez, 2015; Lombardi & Sinatra, 2013; Oversby, 2015), even before the emotional weight of the issue is considered. However, as Ray argues, ‘anguish in response to the material we teach belongs in the classroom, as uncomfortable as it is, and as untrained we might feel to manage it’ (2018, p. 300-301).

Even less environmental education research explores how to respond to climate anxiety and ecological distress. Most of the research we found on this topic was based on individual educators’ personal experiences and insights or literature-based analysis. Siperstein’s reflection (2015) argues that while comfort in the classroom does not necessarily contribute to learning, the pain of disorientation that climate change invokes must be acknowledged to ensure it is not harmful. Moser (2012) argues for increasing students’ capacities to hold paradoxes, to be with others in distress, and that we all need to ‘get real’ about the scale of the challenges. In line with this, Dupler calls for activities that help students explore how they feel (2015), and Lehtonen, Salonen and Cantell (2019) argue that all emotions and experiences should be allowed to be expressed. Pihkala (2017) has suggested that if environmental educators voiced their own uncertainty about the complexities of climate change it would provide students with a sense of comradery, by acknowledging that they are not alone in their grief and anxieties (Pihkala 2017). In addition to acknowledgement, exploration and solidarity, action-oriented strategies are argued to overcome feelings of helplessness (Holdsworth 2019; Siperstein, 2015). Ojala’s empirical research has found that when children perceive their teacher to be accepting of negative emotions, students were more likely to engage in constructive hope (2015). However, as far as we know, no empirical research has investigated how educators perceive their students’ ecological distress, the strategies they are implementing to try to respond to this, or the value or effectiveness of these strategies.

Research aims and design

This research project aimed to explore how climate change educators – broadly defined – are responding to their students’ eco-anxiety and climate grief, and other ecological emotions. Drawing on research from affect theory that suggests climate change can generate embodied experiences that are difficult to name as a coherent emotion (Verlie, 2019b), we chose to keep our definition of ‘emotion’ very broad so as not to preclude potential responses from participants. The main aim was to identify and document the strategies educators engage in order to enable their students to cope with, adapt to, or become resilient to the emotional impacts of ecological degradation, so that others (educators, communicators, activists, therapists, parents, etc.) may learn from their approaches. In order to explore this, we considered a number of sub-questions relating to:

- How do educators perceive their students’ emotions?

- What role do educators’ own emotions play in this?

- What challenges and barriers do educators face when trying to respond to their students’ emotions?

This research project was co-conducted by undergraduate students (Emily, Tamara and Emma) as part of their semester-long capstone project, responding to Cutter-MacKenzie and Rousell’s (2018) challenge to have climate change education research co-led by young people. Blanche, a lecturer in the students’ degree program, proposed and designed the overall project logic and applied for institutional ethics approval before the semester started. During the three months of the semester, Emily, Tamara and Emma refined the research project and survey instrument, recruited participants, and drafted this research paper. The 3-month timeframe was a key constraint influencing research design. This means we have not sought to document to what extent educators are perceiving and responding to their students’ emotions, nor to evaluate the effectiveness of their efforts, but simply to explore some educators’ experiences, insights and strategies.

Thus, we designed a short survey with multiple choice and free text answers and sought participants from a range of educational sectors and institutions, including state and private schools, non-government organizations and universities. We recruited participants through teacher unions and associations, including environmental education networks, and also used personal networks to invite people to participate. This sampling strategy sought to involve those we knew to be thinking about and engaging with these issues, as well as those we did not know but who might be, with a view to gaining insights from those with the most experience and wisdom. Thirty-two people participated in the survey during the six weeks it was open, however not all responded to each question.

Results and Discussion

The vast majority of our participants identified as women (84%), all teach in eastern Australian states (Queensland (8%), New South Wales (8%) and the majority in Victoria (84%)), with the vast majority teaching in a metropolitan context (81%). Most taught at university (57%), followed by secondary schools (both private and public) (31%). Six percent worked in community settings, 1 participant (3%) taught in a primary school, and another in professional development for teachers. 65% were aged between 30 and 49 years old, with 13% under 30 and 22% over 50. Many of our participants had been teaching for less than 10 years (44%), 34% had between 10 and 20 years’ experience, and 22% had more than 20 years’ experience. Had we had more time we may have been able to invite and elicit a broader range of participants, and with that, have been able to seek a representative sample and/or consider how geographic, demographic or contextual factors influenced participants’ responses. However, this was not our project’s aim and we believe the insights generated from the participants are very valuable, in part given the diversity, experience and wisdom regarding environmental education that they provided.

Participants taught in a wide range of courses and subjects, with geography, environmental studies, science and the humanities the most commonly mentioned, with urban design and planning, horticulture, creative writing, politics and education also mentioned. Across this diverse set of disciplines and subjects, 94% of the participants teach about climate change explicitly, and the majority said they taught about mitigation (broadly construed, e.g. including interrogating cultural assumptions) and adaptation, although some (roughly one third) only addressed mitigation. Extinction, biodiversity loss, and plastic pollution were the most frequently mentioned other ecological crises that were taught as curricular content, although there was a much wider range. Educators approached these from a diverse range of perspectives including: social justice, ecological and geological sciences, economic and intersectional perspectives, Indigenous knowledges, animal rights, psychological approaches and posthuman/Anthropocene/multispecies studies lenses. A similarly broad range of pedagogies were mentioned, from nature play, place-based, queer/feminist, and compassionate approaches. Across this quite diverse set of subjects, disciplines and pedagogical approaches, 100% of participants said they were ‘extremely concerned’ – the highest option offered – about climate change.

How do the educators perceive their students’ ecological emotions?

On the whole, our participants put considerable effort into tuning into their students’ emotions. 69% of participants said they paid ‘a lot’ (44%) or ‘a great deal’ (25%) of attention to their students’ emotional responses to the ecological issues they teach about. In response to the open question, ‘how do you gauge your students’ emotional wellbeing generally?’ participants stated that they did this through conversation and other verbal signals such as students’ tone of voice. Many said they specifically initiated verbal check-ins and tried to be approachable so that students would feel comfortable speaking with them when they were not travelling so well. Respondents also said that non-verbal cues such as facial expressions, body language, energy levels, general signs of restlessness and anxiety, and changing behaviours and interpersonal relations were signs they observed in order to ascertain their students’ moods and wellbeing.

We asked participants three versions of a question regarding their perceptions of students’ emotions regarding climate change and ecological crises: what have students told them they have felt; what emotions do the educators perceive students have felt (when students have not verbalised this); and what other embodied, psychological or affective responses have the educators noticed in their students (that are not easily named as an emotion). These questions were each asked as multiple-choice questions, where participants could tick as many options as they liked, and each offered the opportunity for participants to add things we had not anticipated (see Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Across the first two questions, feeling overwhelmed, hopeless, anxious, angry, sad and frustrated were the most commonly noted emotional responses. Feeling hopeful was not reported as highly as these more painful or distressing emotions, and feeling guilty was less common again although still prevalent. Feeling apathetic, bored and resentful were selected more frequently as emotions that teachers perceive students to be feeling than as emotions that students name themselves. Feeling hopeful was noted roughly three times more frequently than feeling optimistic. In the third question, uneasy, restless and low energy which we had offered in the multiple-choice suggestions were each selected almost twice as frequently as animated.

Challenges and barriers to responding to learners’ ecological emotions

Participants identified that failure to attune to, engage with and express emotional experiences ‘can be really dangerous’. As one educator put it, learners can engage in ‘strategic denialism’, stating that their students are ‘not apathetic [but] if it’s so far beyond their sphere of influence, sometimes they just shut down, and don’t engage … [its] a way to protect themselves’, aligning with literature that suggests climate denial can be a coping mechanism (Kristin & Dilshani, 2018). Similarly, one participant noted that ‘big issues like climate change create feelings of hopelessness … but students can’t identify that because we don’t provide enough opportunities to discuss our feelings about these issues so they blame other things’. Another elaborated on this possibility of misdirected emotion, suggesting that ‘the anger/frustration [students feel] can be channeled against the form of authority in the room (i.e. the teacher), representing the system they are angry against.’ Systemic climate denial was omnipresent in participants’ responses, and identified to be a problem even within students’ educational networks:

I find my students seem confused by the disconnect between the ways they are encouraged to see the future – other teachers and parents encouraging them to aspire to careers as though the world will continue the same, and then my class where I suggest it may be very different. I think they don’t know how to hold the two futures they are being presented with, and mostly try to forget or disbelieve a climate crisis view of the future, but also, they can seem resigned to it.

This participant’s insight speaks to Norgaard’s (2011) discussion of everyday climate denial operating through people living a ‘double reality’, where they acknowledge the scientific facts of climate change yet continue with business-as-usual lives.

In the context not only of the massive challenge of climate change but also of systemic denial, responding to the emotional impacts of climate change was acknowledged to be extremely challenging. One participant described how they were ‘wrestling with the tension’ of dealing with the emotional experience of climate change whilst also trying to teach the content of their class, a sentiment echoed by multiple other participants who identified crowded curricula and most especially, time, as a key constraint, similarly to Lehtonen, Salonen and Cantell (2019). As one stated, students’ emotions are ‘hard to gauge because there is little consultation with students after class and that is part of the problem [and it] might also be playing into their experience of isolation.’ Respondents also mentioned concerns about professional norms and the presumption that as teachers they should have both authority over and interpersonal distance from students. One stated ‘I think that they [their students] should get even angrier and take action to fight for their future; but as the teacher, I have to remain “neutral” and cannot take that stance in front of a class’ and another that ‘I felt a bit constrained by my responsibilities and position – if they were friends of mine … the range of emotional expressions available to me would be broader, as would the ways I could follow things up with them afterwards.’ A number of respondents identified that they themselves were struggling with their own ecological distress and had concerns about ‘projecting’ this onto students, as well as being uncomfortable and incapable of being an authority and source on hope, tensions which are similarly identified in the literature (Hufnagel, 2017; Kelsey, 2017; Ojala, 2016). One respondent said that they felt like a ‘failure’ because they were unable to give students answers or solutions due to their own emotional experiences of climate change, and after one discussion ‘had a long cry on my commute home, and wound up cancelling plans I had to meet friends that evening after class.’ Several respondents identified a self-perceived lack of knowledge regarding how to respond to their students’ ecological emotions, aligning with literature that finds that many educators feel as though they do not have the capability to deal with the more emotional aspects of climate change (Lombardi & Sinatra 2013). For reasons such as these, some participants noted they were ‘looking for ways to help students to express these emotions’ because, as another indicated echoing Moser (2012), cultivating ‘emotional capacities to deal with environmental issues’ is an ‘emerging key capacity.’

Educators’ strategies for responding to students’ ecological emotions

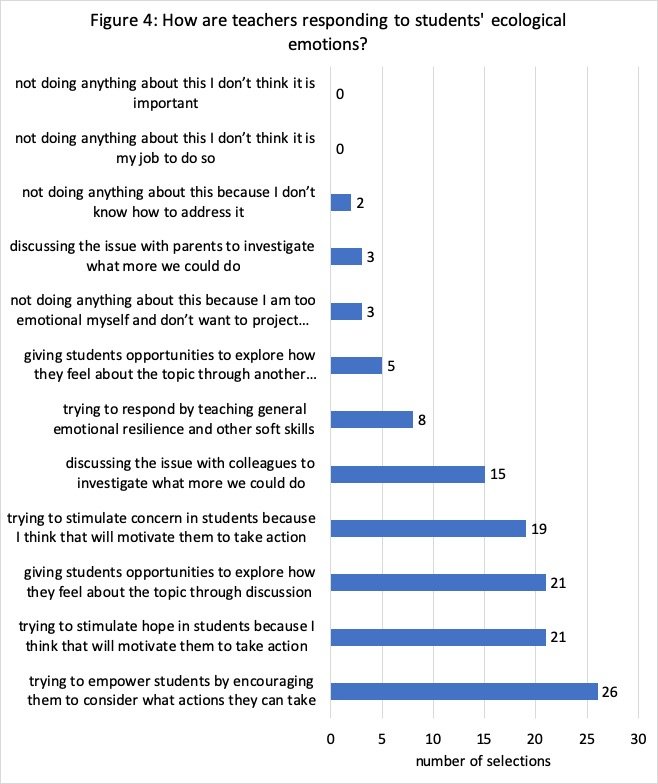

We provided participants with one multiple-choice question asking how and why they are, or are not, responding to the issues they had identified, as well as some open-ended questions that asked about their experiences and strategies for responding to this. As Figure 4 demonstrates, our participants felt that it was important and was their role to respond to this – unsurprising given that they all felt extremely concerned about climate change and had chosen to participate in the survey. While many wrote that they were unsure what to do, only two said they were not doing anything because of this uncertainty and only three that they were not doing anything because of their own emotional distress. The most frequent response selected from this multiple-choice question was that educators are trying to empower students by helping them explore actions they can take. This was closely followed by trying to stimulate hope in students and by giving them space to discuss how they feel. Trying to stimulate concern was selected nearly as frequently as trying to stimulate hope, concurring with research that suggests that both concern and hope are required in order to enable people to respond adequately to climate change, rather than disengage (Ojala, 2016).

The qualitative responses were very rich. We drew on the literature reviewed earlier to make sense of the experiences the respondents shared with us, and did this through attuning to what the respondents were aiming for as well as their strategies for doing this.

Regarding the educators aims, the need to cultivate active hope was mentioned frequently. Most participants argued for the need to ground their students’ hopes for the future in realistic and plausible pathways for change. Some respondents noted that they did not want to ‘infantilize’ their students by promoting an overly optimistic view of climate change, yet were conscious of students searching for reasons for hope among the ‘gloom’ of course material. As one respondent reflected, epitomising the challenges of this work:

A student asked me if I was hopeful, and if he should have hope. I said that we should have radical hope, which is different to blind optimism. I explained the volunteer activities I undertook to help me feel like I was contributing to a positive world. I felt overwhelmed by the emotional burden placed on me to be the ‘authority’ on whether we should have hope (especially considering the circumstances). I was also scared for the person’s well-being, especially if I gave the ‘wrong’ response.

In order to cultivate ‘active hope’, that critical yet elusive combination of concern, inspiration, determination and action, we found educators were employing four key inter-related strategies: engage, validate, support and empower.

Engage

Many respondents emphasised strategies to engage students with the complexities of both climate change and their emotional responses to it, as authors have argued is important (Hufnagel, 2017). For example, educators suggested approaches involving deep reflection, critical thinking, active discussion, reflective journaling, problem solving, debate, transdisciplinarity and the consideration of alternative worldviews or futures. Inquiry and problem-based learning pedagogies underpinned such strategies, as this quotation from a primary educator indicates: ‘students in my classes are critical co-learners in inquiry learning. They have ongoing opportunities for peer discussions relating to their hopes and concerns.’ Engaging with the confronting issues themselves was seen as a way to respond to the painful emotions, such as this participant who ‘sat [students] down and explored the specific issues that were behind the emotional response’ and another who ‘had to hold a discussion about alternatives that they could undertake to not consume fossil fuels. This seemed to help students know that they could actually do something and all hope wasn’t lost.’

Engaging directly with the emotional complexities was also considered beneficial, and this included inquiring, attuning to and exploring them. Seemingly responding to Siperstein’s (2015) call to enable students to explore how climate change feels, one participant said they get students to express how they feel in terms of colours, animals, weather, or other forms that can help express emotions in ways beyond the intellectual. This can be opened up to making body shapes or facial expressions. It could also encompass drawing how they feel.

Another had run a meditation session which they said ‘was really effective in supporting students to gently become attuned to their bodies and how they FEEL climate and relate to it. Students found this activity to be grounding and supported them to acknowledge their somatic/bodily knowing and emotions.’ Another working with primary aged students in a food garden suggested they all write their feelings on a piece of paper and ‘offer it to the compost. … It wasn’t much but its affects were felt two terms later when one child said to me in class, “remember when we wrote love letters to the compost?”’ More straightforward approaches of simply talking about feelings were commonly noted. These approaches stem from an understanding that negative emotions are not problematic in and of themselves, and that providing people with tools to identify and understand their emotions can support them to respond constructively (Amsler, 2011; Affifi & Christie, 2019; Ray, 2018; Verplanken & Roy, 2013).

Validate

A key practice related to and part of engaging people in emotional exploration was the practice of validating students’ emotional experiences. What we term ‘validating’ encompassed acknowledging (such as by listening or otherwise witnessing), normalizing, and sharing vulnerability. Suggested strategies to do this involved opening up discussions amongst peers, where the goal was to name and acknowledge emotions and encourage active listening. In various ways, participants suggested it was important to ‘provide space to discuss [ecological emotions] explicitly’ and that ‘this is not about brushing aside or trying to deny these emotions, but rather acknowledging them.’ Normalising what arose in those spaces of witnessing was also advocated: ‘listening and acknowledging that it is hard and that no one really has a definitive miracle solution.’ This participant elaborates on what such normalization might look like: ‘I do not minimise what they’re feeling, nor do I try and push them, hurry them along into hope.’ Normalising painful and distressing experiences often occurred through sharing people’s vulnerabilities, whether that be the educator’s or the whole group’s experiences. One participant ‘opened up the discussion for all of us to hear each other out. Primarily so we could give voice to what we were each feeling.’ Another tries ‘to be real about my own struggles with this. I often end up on the verge of tears in class when we’re watching videos or talking about climate change and I let them see that and try to talk about how I manage the grief and fear.’ Sharing vulnerabilities was understood to reduce the sense of isolation that can accompany climate grief (Cunsolo Willox, 2012; Pihkala, 2017), as one participant suggested: ‘when there is space to process and engage with the emotional experiences of climate change, it generally has a positive impact. The importance I find is normalising and cultivating emotional solidarity within the classroom.’ Educators clearly found the practice of ‘creating space’ for emotional exploration and validation important, with frequent references to it. One elaborated on how this proceeded after starting a group discussion: ‘I allowed the energy of the room to be what it needed to be. I then asked the students if they needed a break from discussing the specific concern we were engaging. We took a break from it.’ In this example, taking a break also demonstrated validation of students’ experiences, and by acknowledging their own personal emotional intelligence also contributed to supporting and empowering them.

Support

From engaging with and validating learners’ ecological distress, our respondents also strove to support students to cope with, adapt to, or manage these emotions. This involved the emotional labour of ensuring students felt cared for (Lehtonen, Salonen & Cantell, 2019; Lloro-Bidart & Semenko, 2017), helping students build caring communities with their peers, and enabling them to resource themselves appropriately. For example, one participant mentioned they let ‘students know that I have a duty of care to ensure that their engagement with our learning about climate change is supported and not traumatizing.’ This sense of care is also demonstrated by the following educator who identifies that individualised and guilt-inducing responses can be damaging, as Kelsey has argued (2017): ‘don't overburden them with a sense of isolated, individual responsibility BUT help them connect [to] an interconnected community. Steering thoughts away from individual impacts, and using team building activities, helps to alleviate feelings of isolation.’ Cultivating a ‘welcoming and supportive environment in the classroom such that they are comfortable in sharing their emotions’ was seen to be a form not only of validating their experiences but of developing community. One participant told of one effort to do this, and that they sought to ensure students were aware that community can be a source of support: ‘we went outside and all brought food to share that held some significance to us. This was a way to build community…we explicitly discussed the importance of building these connections and discussing the emotional responses inevitable to our work.’ While building social connection among cohorts was advocated, so was supporting students to identify what works for them personally: ‘I encouraged students to do what they needed to do to help resource themselves.’ Another provided suggestions of things that might ‘help them look after themselves, such as taking active rest, applying for extensions where possible, taking deliberate time out from study commitments and spending time with things that matter to them’, and another introduced ‘mindfulness elements to help build [their] awareness and capacity to resource themselves.’

Empower

A very strong theme in participant’s suggested strategies was the importance of empowering people to counteract feelings of hopelessness. Techniques to do so included exploring alternatives to the status quo, connecting them to activist or similar groups, showcasing role models, and providing and exploring opportunities. One educator tries to ‘prompt some reflection on how we might need to think differently’ and another noted that they ‘have started to incorporate “alternatives”’ into their classes: ‘alternative political systems, alternative economies, social movements, social justice, etc.’ The premise of this was ‘to give them ways to get involved,’ a strategy echoed by another teacher who said they ‘tend to encourage students to think about the opportunities for creating positive change’. Helping people identify, explore and take up ‘opportunities’ was a frequent theme in the respondents’ strategies. For some, this involved possibilities for individual action. For example, one educator provides students ‘with opportunities to make changes in their own lives [by outlining] the choices they have to reduce carbon and ecological footprints.’ However, many noted that empowerment is best achieved through connecting students with others so that they can engage in collective environmental action, aligning with Kelsey’s (2017) and Nairn’s (2019) arguments for collectivizing hope. One educator suggested getting ‘them to start a group at school’, and another had done this, by helping their students work ‘together as a team within the school to implement some mitigating strategies to reduce the school’s carbon footprint,’ strategies argued to be effective in the literature (Monroe et al., 2017). Others advocated ‘linking them up with youth groups that are taking action,’ and another more specifically suggested showcasing role models they can look up to and emulate: ‘get young climate activists in to talk to them,’ a strategy also suggested by Ojala (2012b). As this final quotation emphasizes, cultivating active hope requires supporting students to participate in collective action:

They must be empowered to be hopeful; they must be given tangible opportunities to engage in hopeful activities. This at my school includes … participating in Marine Mammal Foundation workshops, being active members of our Landcare Group, being part of our rainforest project Instagram posts.

However, despite educators’ efforts to engage, validate, support and empower students, many acknowledged that sometimes this does not work, and that they are not entirely sure of what they are doing. One example emphasized this:

I gave the space in the class for students to express what they feel and their anger. But it came to a dead-end, with everyone’s hope ending very low. I could feel their frustration and hopelessness, but struggled finding a way to channel it in anything constructive without sounding naive by saying positive messages that don’t mean much given the challenges we face.

Another questioned their own efficacy: ‘I don’t know how effective or useful or responsible it is, but my main strategy at this point is listening. … But it’s clumsy, I’m clumsy with it’, echoing Siperstein’s (2015) discussion of such challenges. One emphasized that their approaches to this are still in development: ‘I am keen to explore weekly check-ins and check-outs in each class. I want to implement some mindfulness based meditation and movement options we can engage with in class in amongst the teaching of content.’

Conclusion

This study provides a beginning point for exploring how educators can practically navigate the interpersonal complexities of cultivating active hope in a context of increasing ecological distress. The emotions the participants in this study identified in their students are closely aligned with those identified within the literature (Albrecht 2011; Ojala 2016; Pfautsch & Gray 2017; Strife 2012; Verlie 2019a). By approaching this from the perspective of educators whose role is not to soothe but to enable action-competence and lifelong learning (Ojala, 2016; Ray, 2018), we have identified some valuable strategies for supporting people to ‘learn to live with climate change’ (Verlie, 2019a). Through the work to engage people in exploring their ecological emotions and sitting with them, rather than seeking to heal them (Lehtonen, Salonen & Cantell, 2019; Ojala, 2016; Siperstein, 2015) or ignore their presence altogether, educators were supporting their learners to develop strategies for navigating the complex emotional and interpersonal terrain that is only going to heighten as climate change intensifies. The wide variety of pedagogies and the intensely personal and philosophical discussions these educators had with their students demonstrate a considerable move away from the ‘science deficit’ approach which so often characterizes climate change education (Cutter-MacKenzie & Rousell, 2018).

It is clear from this study, as well as from the literature, that many climate change educators feel that they need more support and resources to be able to engage people with such a complex topic (Lombardi & Sinatra, 2013; Reid, 2019; Swim & Fraser, 2013). While not seeking a ‘solution’ and conscious that painful emotions are not necessarily problematic, many respondents expressed their trepidation over whether anything they could do would help their students live with the increasingly heavy burden of climate grief and ecological anxiety. While we did not ask educators what they thought would help them do this better (a regrettable oversight in our survey design), we believe the following suggestions are valid places to start.

Our respondents noted that a lack of time was a key barrier to them being able to engage appropriately with their students’ ecological emotions. If educators were better supported to teach climate change across the curriculum and in transdisciplinary ways, this could potentially increase the amount of time available for the delicate interpersonal practices that are needed to respectfully and carefully support students to explore, identify and respond to their concerns about their own futures. Professional development to enable teachers to better support student emotional wellbeing in general – for example, mental health first aid courses – may also be useful. Teachers and educators clearly need their own emotional wellbeing to be considered and supported as well (Kelsey, 2017; Lloro-Bidart & Semenko, 2017; Ray, 2018), and programs and initiatives that can offer that would no doubt be beneficial. Ultimately, the only ‘cure’ for ecological distress is to prevent ecological destruction happening in the first place. Given our respondents’ suggestions that collective environmental action contributes to active hope and thus emotional wellbeing, and that educational institutions are often community hubs with considerable political and social capital, institution-wide measures that enable students to participate in order to collectively tackle ecological crisis could be effective and achievable win-wins.

There is still very little research regarding what is happening at a practical level to respond to ecological distress, whether in education or beyond. This study is a preliminary and exploratory offering in that regard. We believe the strategies of engage, validate, support and empower are very useful in terms of cultivating active hope and could be valuable to those seeking to support people to engage with climate change well beyond the realm of formal education. However, there is a lot more research required given this is an issue that is going to escalate in the coming years. Youth climate strikes demonstrate the extreme level of concern among young people around the globe, with Greta Thunberg advocating not for hope, but for panic. Our research has not investigated to what extent our educators’ efforts were ‘successful’ or ‘effective’, and while such goals may be unachievable and even undesirable for such a tenuous, relational issue, research exploring what ‘works’ and what does not, and in which contexts, would be very valuable. Research exploring the capacities and experiences of those who have lived with and managed ecological distress over a number of years, and what experiences, insights, philosophies and practices have supported them to maintain their wellbeing and/or environmental action, would also benefit those of us seeking to cultivate active hope in our communities.

References

Affifi, R., & Christie, B. (2019). Facing loss: pedagogy of death. Environmental Education Research, 25(8), 1143-1157. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2018.1446511

Albrecht, G. (2011). Chronic Environmental Change: Emerging ‘Psychoterratic’ Syndromes. In Weissbecker, I. (ed.), Climate Change and Human Well-Being, 43-56. New York, NY: Springer.

Amsler, S.S. (2011). From ‘therapeutic’ to political education: the centrality of affective sensibility in critical pedagogy. Critical Studies in Education, 52(1), 47-63. Doi: 10.1080/17508487.2011.536512

Chapman, D. A., Lickel, B., & Markowitz, E. M. (2017). Reassessing emotion in climate change communication. Nature Climate Change, 7(12), 850-852. doi:10.1038/s41558-017-0021-9

Cianconi, P., Betrò, S., & Janiri, L. (2020). The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: A Systematic Descriptive Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(74), 1-15. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

Corner, A., Roberts, O., Chiari, S., Völler, S., Mayrhuber, E.S., Mandl, S. & Monson, K. (2015). How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 6(5), 523-534. doi: 10.1002/wcc.353

Cunsolo Willox, A. (2012). Climate change as the work of mourning. Ethics & the Environment, 17(2), 137-164. doi:10.2979/ethicsenviro.17.2.137

Cutter-Mackenzie, A., & Rousell, D. (2019). Education for what? Shaping the field of climate change education with children and young people as co-researchers. Children's Geographies, 17(1), 90-104. doi:10.1080/14733285.2018.1467556

Dupler, D. (2015). On the Future of Hope. Journal of Sustainability Education, 10, 1-5

Ecclestone, K. & Hayes, D. (2008). The dangerous rise of therapeutic education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Grauer, S. R. (2020). Climate change: The thief of childhood. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(7), 42-46. doi:10.1177/0031721720917541

Hayes, K., Blashki, G., Wiseman, J., Burke, S., & Reifels, L. (2018). Climate change and mental health: Risks, impacts and priority actions. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 12(1), 28-40. doi:10.1186/s13033-018-0210-6

Head, L. (2016). Hope and grief in the Anthropocene: Re-conceptualising human–nature relations. New York, NY and Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

Herman, B.C., Feldman, A. & Vernaza-Hernandez, V. (2017). Florida and Puerto Rico Secondary Science Teachers’ Knowledge and Teaching of Climate Change Science. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 15(3), 451–471. doi: 10.1007/s10763-015-9706-6

Holdsworth, R. (2019). Student agency around climate action: A curriculum response. Ethos, 27(3), 9-14.

Hornsey, M. J. and K. S. Fielding (2016). A cautionary note about messages of hope: Focusing on progress in reducing carbon emissions weakens mitigation motivation. Global Environmental Change, 39, 26-34. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.04.003

Hufnagel, E. (2017). Attending to emotional expressions about climate change: A framework for teaching and learning. In D. P. Shepardson, A. Roychoudhury, & A. S. Hirsch (Eds.), Teaching and learning about climate change: A framework for educators, 59-71. New York, NY and Milton Park: Routledge.

IPCC. (2018). Global warming of 1.5°C: Summary for policy makers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/

Kelsey, E. (2017). Propagating collective hope in the midst of environmental doom and gloom. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 21, 23-40.

Kristin, H., & Dilshani, S. (2018). Climate change skepticism as a psychological coping strategy. Sociology Compass, 12(6), 1-10. doi:10.1111/soc4.12586

Lehtonen, A., Salonen, A. O., & Cantell, H. (2019). Climate Change Education: A New Approach for a World of Wicked Problems. In J. W. Cook (Ed.), Sustainability, Human Well-Being, and the Future of Education, 339-374. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Li, C., & Monroe, M. C. (2018). Development and validation of the climate change hope scale for high school students. Environment and Behavior, 50(4), 454-479 doi:10.1177/0013916517708325

Li, C. J., & Monroe, M. C. (2019). Exploring the essential psychological factors in fostering hope concerning climate change. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 936-954. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1367916

Lloro-Bidart, T., & Semenko, K. (2017). Toward a feminist ethic of self-care for environmental educators. The Journal of Environmental Education, 48(1), 18-25. doi:10.1080/00958964.2016.1249324

Lombardi, D., & Sinatra, G. M. (2013). Emotions about teaching about human-induced climate change. International Journal of Science Education, 35(1), 167-191. doi:10.1080/09500693.2012.738372

Macy, J. & and Johnstone, C. (2012). Active hope: How to face the mess we’re in without going crazy. Novato, CA: New World Library.

Manning, C., & Clayton, S. (2018). Threats to mental health and wellbeing associated with climate change. In S. Clayton & C. Manning (Eds.), Psychology and climate change, 217-244. London, San Diego CA, Cambridge MA and Oxford: Academic Press.

Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A., & Chaves, W. A. (2017). Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 791-812. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842

Moser, S. C. (2012). Getting real about it: Meeting the psychological and social demands of a world in distress. In D. R. Gallagher (Ed.), Environmental Leadership, 900-908. Los Angeles CA, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washing DC: SAGE Publications.

Moss, S. A., & Wilson, S. G. (2015). The Prevailing Origin of Psychological Problems in Young People: A Dissociation from the Future. Issues in Social Science, 3(1), 15-34. doi: 10.5296/iss.v3i1.6768

Nairn, K. (2019). Learning from Young People Engaged in Climate Activism: The Potential of Collectivizing Despair and Hope. YOUNG, 27(5), 435–450. doi:10.1177/1103308818817603

Norgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in denial: Climate change, emotions, and everyday life. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press.

Ojala, M. (2012a). Regulating Worry, Promoting Hope: How Do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Cope with Climate Change? International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 7(4), 537-561.

Ojala, M. (2012b). Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environmental Education Research, 18(5), 625-642. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.637157

Ojala, M. (2015). Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations With Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation. The Journal of Environmental Education, 46(3), 133-148. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662

Ojala, M. (2016). Facing anxiety in climate change education: From therapeutic practice to hopeful transgressive learning. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 21, 41-56.

Oversby, J. (2015). Teachers’ Learning about Climate Change Education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 167, 23-27. doi: /10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.637

Pfautsch, S. & Gray, T. (2017). Low factual understanding and high anxiety about climate warming impedes university students to become sustainability stewards: An Australian case study. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 18(7), 1157-1175. Doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-09-2016-0179

Pihkala, P. (2017). Environmental education after sustainability: Hope in the midst of tragedy. Global Discourse, 7(1), 109-127. doi: 10.1080/23269995.2017.1300412

Pihkala, P. (2018). Eco-anxiety, tragedy, and hope: Psychological and spiritual dimensions of climate change. Zygon, 53(2), 545-569. doi: 10.1111/zygo.12407

Pihkala, P. (2019). Climate Anxiety. Helsinki: MIELI Mental Health Finland.

Ray, S. (2018). Coming of age at the end of the world: The affective arc of undergraduate environmental studies curricula. In K. Bladow & J. Ladino (Eds.), Affective Ecocriticism: Emotion, Embodiment, Environment, 219-399. London and Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Reid, A. (2019). Climate change education and research: possibilities and potentials versus problems and perils? Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 767-790. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1664075

Russell, C., & Oakley, J. (2016). Engaging the emotional dimensions of environmental education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 21, 13-22.

Siperstein, J. (2015). Finding hope and gratitude in the climate change classroom. Journal of Sustainability Education, 10, 1-17.

Stevenson, K., & Peterson, N. (2016). Motivating action through fostering climate change hope and concern and avoiding despair among adolescents. Sustainability, 8(6), 1-10. doi: 10.3390/su8010006

Strife, S.J. (2012). Children's Environmental Concerns: Expressing Ecophobia. The Journal of Environmental Education, 43(1), 37-54. Doi: 10.1080/00958964.2011.602131

Swim, J. K., & Fraser, J. (2013). Fostering Hope in Climate Change Educators. Journal of Museum Education, 38(3), 286-297. doi:10.1080/10598650.2013.11510781

Taylor, S.E. & Stanton, A.L. (2007). Coping Resources, Coping Processes, and Mental Health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 377-401.

Tschakert, P., Ellis, N. R., Anderson, C., Kelly, A., & Obeng, J. (2019). One thousand ways to experience loss: A systematic analysis of climate-related intangible harm from around the world. Global Environmental Change, 55, 58-72. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.11.006

UNESCO. 1977. Tbilisi Declaration:Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education. Available at https://www.gdrc.org/uem/ee/Tbilisi-Declaration.pdf

Verlie, B. (2019a). Bearing worlds: learning to live-with climate change. Environmental Education Research, 25(5), 751-766. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1637823

Verlie, B. (2019b). “Climatic-affective atmospheres”: A conceptual tool for affective scholarship in a changing climate. Emotion, Space and Society, 33, 100623. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2019.100623

Verplanken, B., & Roy, D. (2013). “My Worries Are Rational, Climate Change Is Not”: Habitual Ecological Worrying Is an Adaptive Response. PLoS ONE, 8(9), 1-6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074708

Whitehouse, H. (2017). Point and counterpoint: climate change education. Curriculum Perspectives, 37(1), 63-65. doi:10.1007/s41297-017-0011-0